What? A Hollywood-style formation drama: “Saving Bugsy Bendell”

Where? 40,000ft in a No.IV (AC) Sqn pair from RAF Jever, 2nd Tactical Air Force

When? Second sortie on 28th March, 1958

Why? The Hunter’s pre-modified oxygen masks and connector system

On that memorable day 54 years ago, when flying from RAF Jever, my second sortie of three started quite normally. With two full inboard drop tanks the F Mk 6 took 7 minutes, so an extra 75 seconds from wheels roll to make 40,000ft. Within what seemed to me, both then and now, like a slowly developing Hollywood film drama, events rapidly unfolded, literally out of a bright blue sky but this way up above a lot of clouds. It had been a standard pairs take-off and climb-out through these several layers of cloud, mostly thick, deep and bumpy, with eventual tops above 30,000 ft.

Fg Off Tony ‘Bugs’ Bendell being briefed during a IV(AC) Squadron Sylt Armament Practice Camp by Fg Off Alan Pollock (right in dyed, rifle green 26 (AC) Sqn flying suit) probably in March 1958

Fg Off Tony ‘Bugs’ Bendell was leading this particular sortie. At that time, from our general estimation, we all respected ‘Bugs’ as a fascinating individual example (if not perhaps even the real exemplar) of someone often deceptively diffident on the ground, who immediately he lifted his Hunter’s wheels up, seemed to become a different, highly focused and switched on fighting individual. This shared view of mine – I knew well his capabilities – helped save several precious seconds and maybe even saved another’s life that day, in an incident which helped accelerate improvements to our Hunter’s oxygen. Below: Fg Off Tony ‘Bugs’ Bendell being briefed during a IV(AC) Squadron Sylt Armament Practice Camp by Fg Off Alan Pollock (right in dyed, rifle green 26 (AC) Sqn flying suit) probably in March 1958. At one stage in 1957 the Squadron had its full complement of one Squadron Commander Sqn Ldr Ray Chapman, two flight commanders in Lt R W ‘Bob’Parkinson RN and Flt Lt John Sutton (the future AM Sir John Sutton KCB), and all the rest were 22 Flying Officers, showing a different reality in those mid-1950s from later eras. The Squadron too was partly swollen by the effects of the Sandys Axe and efforts to extend people who had invested in cars not being hammered for tax by premature return to UK. 1957 also brought one further and almost unnoticed watershed that year – on 26 at Oldenburg we had almost the last example of a declining breed, previously a more normal presence on many front line squadrons, a Sgt Pilot. Shiny Four, a few months later and still at Jever, for a short time only had just two married men on the whole squadron’s aircrew strength including the new bachelor Boss Sqn Ldr Tim McElhaw, again a contrasting ratio compared with today’s RAF! One last item of historical note was that at some stage in1958, with too many 2nd TAF pilots often off flying with temporary injuries or worse after the more riotous and violent Dining-in Night mess games of those days, strict orders came down with immediate effect from very high level – no more High Cockalorum, instantly banned, with those routine challenges between squadrons but other less injurious ones did remain to enliven our Mess life. Shortly beyond this we would also be addressed one Met Briefing morning by our NZ Station Commander, Gp Capt S W R ‘Sid’ Hughes (later AM Sir Rochford Hughes KCB CBE AFC, )in early 1958 to say that Anglo-German relations were now to be more actively encouraged, perhaps linked with the beginning of the RAF Training Mission and the realisation that West Germany would need to become a much stronger component within NATO.

That spring in 1958 there were three specific trends I instantly recall. Firstly an interceptor fighter basically at that time was the aeronautical design product to swiftly clinb, carry and deliver lethal gunnery force to eliminate hostile aircraft at any altitude. Perhaps inevitably with our Mk.6s and standard usage of our 100 gallon inboard drop tanks, there was then a diminishing use of that star demonstration routine and one of the Hunter’s finest attributes, the operational turn-round, with races at flight or squadron levels. These had been almost invariably put on for visiting VIPs and squadron team practices in the Hunter Mks 1,2, 4 &5, but this was declining partly from its now becoming ‘old hat’, even if still so exciting to watch. Having said that, though, I do clearly remember demonstrating, within the 26(AC) Squadron team at G?tersloh on an exercise in the following year, that ‘just possible’ under 10 minutes from touch-down, complete re-fuel and pack change re-arming operational turn-round to taxy out and airborne lift-off again for the follow up sortie. Secondly there were increasingly competitive rules and independent timing from crewroom alerts to airborne lift-off on our operational scrambling for Battle Flight with fully armed aircraft and by now our high velocity HE ammunition. On 7th April 1958 at Jever, with No. IV (AC) Squadron and ten days beyond this special sortie with Bugs, I have one Battle Flight scramble time noted, when paired with Dickie Barraclough, in which we recorded 2 minutes and 33 seconds, this an actual scramble from the upstairs crewroom to one’s aircraft personally prepared, checked, with its pre-adjusted parachute and security harnesses laid waiting and alert crews – this was a good time when also including our start up and that long, parallel taxy track to our being airborne onto our eastwards heading. This proved to be an errant USAF DC-4 north of L?beck. For our ‘5 minutes readiness’, three and a half minutes was a respectable time from squawk box notification in Shiny Four’s first floor crewroom to the pair’s ‘wheels up’ and by which time the secondary Battle Flight pair would have come from their 30 minutes’ to a 5 minutes’ readiness state.

The third elements recalled at that time on the squadron were that in our formation pairs, virtually as the wheels were being retracted immediately after take-off and when mere feet off the ground, both leader and the No.2 would both gently bank outwards from each other, so as to be straight into wide battle formation for defensive cross-coverage against the vulnerable bounce on take-off and when initiating the climb. Later a few of us too began speeding up the first part of our ‘one versus one’ simulated combat initiations by carrying out our 45 or 60 degrees ‘outward split’ manoeuvres for one minute or ninety seconds near the top but while still continuing our .9M or .85M climb. I believe this was also the case on that day but I could be wrong . . . forgive a change in prevailing orthodoxies everything as sometimes, like fashion, they could die so young!

Absolutely nothing untoward nor any intimation of problems in Bugsy’s leading occurred on climb-out until beyond our outward climbing or level split and inward turn from our 15 miles separation at altitude, by then blind to each other and when our 1 v 1 practice combat game was now on. Occasionally pairs or fours in those days could be on different channels to enhance the realism but this was already becoming marginal practice for obvious flight safety reasons, even in that rather splendid period (I think!), when virtually anything airborne out of an airway (far fewer airways and those all much lower) was fair game for a dogfight or a bounce even into the circuit at times. Initial sighting was often important to dictate positional tactics and maintain one’s initial advantage. For normal ‘one versus one’, as opposed to fighting in pairs or fours, we would always stay ‘stumm’, on sighting and beyond in those often critical first couple of scissor crossovers, unless one was teaching youngsters or, as in the USAF vernacular of the day so shortly afterwards, the ‘FNGs’, those ‘Fairly New Guys’! Within two easy reversals and obviously not feint manoeuvres by Bugs, soon and far too easily I was behind and about to take film, when I instantly realised that Bugs’s aircraft was not being flown either aggressively or defensively. Thankfully, in an instant and certainly without any required brilliance on my part, anoxia was obviously most likely to be his problem. I called “Red Lead from Red Two” but absolutely no reply came back. I then called him Bugs and raised the authority level in my tone of voice, as we had only seconds to act.

Two rapid imperatives, oxygen supply and descent, now conflicted in priority. I ordered him to check that his oxygen connections were fully made and to ensure 100% oxygen and his emergency pressure toggle was switched over left or right to extra full flow, with the last thing for him to pull up to turn on his emergency oxygen bottle supply. It was imperative for me to get Bugs down mighty fast but there were at least three or four layers of quite deep clouds for us to complicate the penetration between us and his personal safety six or seven vertical miles below. Straightaway I told him to level his wings, ordered his dive-brakes out, his throttle back and, seeing his compliance, we began to dive on that heading with me out on his starboard side, watching him like a hawk To my great relief and with his flying like some sleeping automaton, Bugs began silently to obey, following each of my instructions slowly but without ever one single squeak of reply, which certainly kept the drama’s tension up.

While we needed both of us to go straight down as fast as we could, I had to avoid Bugs now losing control or my losing him in those thick cloud layers below us. I realised straightaway that we would have to go down in at least three set stages turning starboard onto particular headings above and when back into those brief two clear air and sandwich gaps lower down. We would then roll back level-winged just before we went back into the next clouds, so as to keep descending safely but also for us to end up positioned near the coast and over the sea, to allow maximum clearance for any recovery if he or we subsequently lost control before breaking out OK underneath the cloud base.

We plunged fairly steeply into that first top layer of cloud and not only had I to stay formating, safely tucked in onto his starboard wing, but I noticed immediately, in that nebulous gloom, that I would also have to do all ‘his’ instrument flying in the cloud, now for my own safety too. I was telling Bugs to correct his bank left or right to keep him in his dive with his wings level but, while still in close formation in the cloud, I required frequent totally unorthodox, snatched rapid-scan glimpses across and down at my own six master instruments, before instantly transferring back to our standard formation position close to his wingtip and sighting along Bugsy’s starboard wing’s aileron hinge line. Once more after those few regular but so vitally important cross-checks back into my cockpit’s instruments, miraculously every time I had instructed him to bank left or right, ease or steepen his descent, Bugs did whatever was ordered – but never once was there one whisper in return. Out in echelon starboard, I called my instructions and, with a reassurance not always felt as I continued my pattered commentary to him.

Three times we had to change direction between cloud layers as we went through these deep layers of cloud., successively completing our descending turns in the clear, as we went through those brief gaps but always having to anticipate having our wings unbanked or very nearly so before the next IMC stage. This whole developing plot seemed to be, as it would to anyone, like some corny, or maybe not so corny, Hollywood film drama that I was watching, as I kept re-checking his wings level in the descent or reminding him once more to check his oxygen flow and connections. All the way down without one iota of response except slow but obvious responses to my firm instructions, his bank thankfully came on and off exactly as requested. Corny though this Hollywood film might have seemed, the nagging and obvious worry was, were we going to manage a happy ending – in our descent I was not at all certain on that specific point!

Then quite suddenly we broke out through and below that last layer with both our aircraft pointing still steeply downwards at the sullen grey-green surface of the North Sea below our Hunters and 15 miles off the German coast. As I eased out slightly to begin our turning even further starboard now back onto our heading for Jever, I had a second surprise and this one with a slight barb in its tail. As we passed exactly through 7,000ft, Bugs awoke most abruptly from his dumb, distant reverie and lack of most consciousness – not only that but he had the amazing, instant cheek to say, rather haughtily, that he was resuming leadership of our pair!

Inevitably all the way back, I watched every move of this reincarnated Bugs Bendell even more like a hawk but all seemed to go surprisingly well. We did end up with a foreshortened sortie for once but I certainly was not going to quibble as we ran back in to break into the circuit with much more fuel than usual to land back onto Jever field’s long runway, deep in that forest west of Wilhelmshaven. The authorisation sheet was signed in by the pair of us as ‘DNCO’, Duty Not Carried Out, but, in its turn and at the flickering end of this ‘film’, that also mattered not one iota.

Bugsy’s Special Occurrence Report within his autobiographical book, “Never in Anger”, read: “During the climb I noted that all oxygen indications were satisfactory, the flow was normal and 100per cent oxygen was selected. Shortly after levelling at 37,000ft we split for air combat and the next thing I remember was regaining consciousness at 7,000 ft. descending, with the throttle closed, air brakes out, and oxygen selected to emergency We continued the sortie below 10,000ft. I made a normal approach and landing at base. Alan Pollock, my No.2, was able to fill in the details: after too easily gaining the ascendancy in the dogfight and seeing my aircraft roll inverted into a steep dive, Al asked if I was OK. Receiving no R/T reply he immediately suspected anoxia and, using my own name instead of the official call-sign, he instructed me to pull my emergency oxygen supply and reconnect my main tube, which I apparently silently obeyed. Formating on my wing tip, and flying on instruments through three separate cloud layers Al brought the formation safely down to 7,000 feet over the North Sea.”

What turned out extremely well, after this incident and the medical inspection of Bugs, was a train of urgent flight safety actions set in motion which followed. This accelerating the dog clip, which we all were soon using to prevent oxygen disconnection and that other modification, which immediately alerted one by instantly stopping any breathing, if one’s oxygen supply to the mask did somehow become disconnected. This improved oxygen system rapidly provided an instant major wake-up call to urgently reconnect or switch to one’s emergency oxygen supply. This must have prevented further loss of life and, one imagines, fewer of those otherwise unexplained aircraft and pilot losses in the accident statistics, which, when seen, had not always been aircraft diving out of cloud.

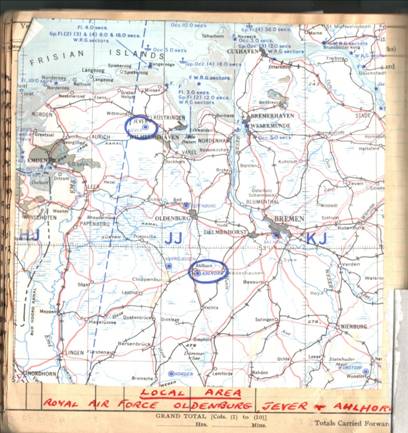

Our 1957 NW Germany 1:1,000,000 scale high level flying map from my logbook. RAF Jever in the north and Ahlhorn in the south have been ringed. The airfield at Oldenburg can be seen more than halfway between these bases, with Nordhorn bottom left and Wunstorf bottom right on this small section.

Recent Comments